본문

-

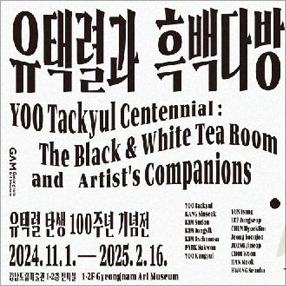

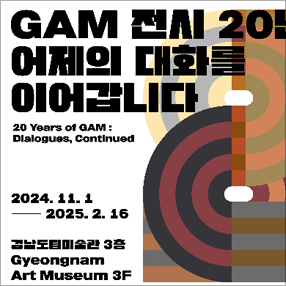

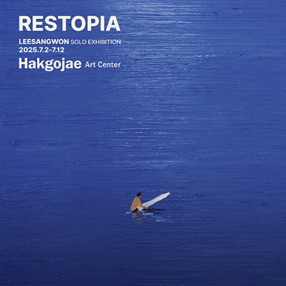

전시포스터

-

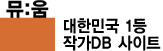

김지평

묘-향(妙-鄕) 150_300cm, 혼합매체, 2015

양아치

뼈와 살이 타는 밤 C-프린트, 디아섹, 150_100cm, 2014

류성실

대왕트래블 칭쳰 투어- 김첨지 리바이벌2019 단채널 비디오, 25분, 2019

원성원

IT 전문가의 물풀 네트워크 C-프린트, 178x297cm, 2017

전혜림

이어진 산수L 캔버스에 유화, 162.4x130.5cm, 2020

최하늘

일필휘지 조각_큰 풍경 가변설치, 혼합매체, 2015

Press Release

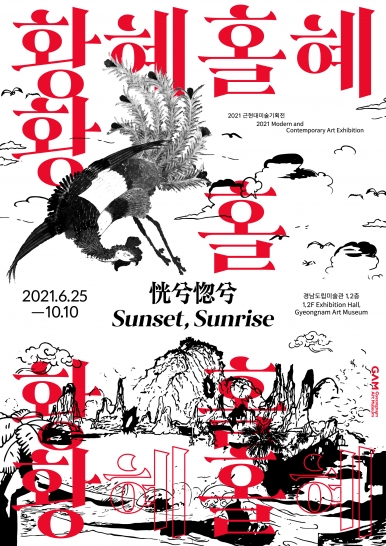

2021 근현대미술기획 《황혜홀혜 恍兮惚兮》

한국 근현대미술의 역사에서 19세기말 조선미술계의 시대적 요구는 봉건성 극복이나 근대성 획득 보다는 민족 자주성 확립이 최고의 미적 가치였다. 19세기말에서 20세기 초 밖으로는 외세의 침략과 안으로 계급 모순이 거세지면서 이러한 미적 가치에 대한 시대 인식은 조선의 문인화를 중심으로 더욱 강화 되었다. 그러나 개항과 함께 조선 사회 계급 구조의 급격한 변화 속에서 전통 사상에 대한 충분한 반성이나 새로운 미술에 대한 견고한 해석 없이 ‘근대화는 곧 서구화’라는 급진적이고 단편적인 인식으로부터 서구 중심의 근대예술 체계를 받아들였다. 전통으로부터의 내적 동인 없이 외부의 정치 사회적 조건에 맞물려 ‘서화’에서 서구의 ‘미술’로 재편되면서 ‘서화’는 물론 500년 조선 서화 미술의 종결이자 새로운 물결이라 할 수 있는 ‘민화’ 역시 그 가치를 공고히 하지 못한 것이 사실이다.

우리가 알고 있는 민화(民畵)라는 명칭은 민중에 의해 그려지고 민중을 위한 그림이라는 의미로 일본의 미학자이자 민예운동가인 야나기무네요시의 주장에 따라 명명되면서 지금까지 통용되고 있다. 물론 현재 민화는 서민화를 포함, 궁중장식화, 화원그림까지 두루 포괄하는 개념을 담고 있지만 서민의 그림으로써 민화가 그 이름이 갖는 단순한 의미를 넘어 매우 개성 있고 해학적이며 불가사의한 조형성이 배어있다는 것에 주목할 필요가 있다. 민화의 조형 형식은 다시점을 통해 추상과 구상을 넘나들며 대상을 해체 전복 시키는 회화성과 수많은 도상으로 저마다의 의미를 가지며 사회상을 담아내는 시대성까지 드러내고 있다. 아울러 민화의 작가는 그림을 배운 화공이 아니었기에 사회적으로 규정된 어떤 원칙이나 법칙을 따르기보다 스스로 해결책을 찾는 작자의 자유의지가 그 익명성을 담보로 더욱 새로운 방식으로 전개 되었다. 특히 민화에서 사실성의 여부나 표현의 정교함, 생략과 왜곡, 유치한 표현까지 허용되는 것은 문인화적 사고에 기인한다고 볼 수 있으며 이러한 맥락은 이 후 현대미술에서 어렵지 않게 찾아 볼 수 있다.

18세기 후반과 19세기를 거치며 제작된 민화는 급변하는 시대에 의지할 곳 없는 민중이 세속적 욕망에 매달리며 인생의 궁극적이고 가장 인간적인 소망을 담아낸 것이라 할 수 있다. 행복, 사랑, 부귀, 장수, 영생 등 인간의 보편적 가치를 실현하고자 하는 시대의 욕망은 좋은 삶_이상향에 대한 염원으로 이어지며 민화의 새로운 세계로 확장되었다. 또한 인간과 자연의 조화, 출세와 부귀, 자손번성, 영웅담, 무병장수, 현실과 꿈 등 인간의 삶과 죽음을 사유하는 근원적인 욕망을 아우르고 있다. 이것은 비록 사대부의 고급문화를 모방하고자 했고, 그들의 사의적(寫意的)그림을 차용하였으나 문인화와는 또 다른 아름다움이 개방성과 익명성을 통해 특별한 의미를 부여 받는다. 이는 시대를 외면하거나 도피하는 것이 아니라 우리의 유구한 전통으로서 고대부터 이어져온 예술 세계를 통해 급변하는 현실세계를 내일의 꿈으로, 믿음으로, 희망으로 그려내며 새로운 세계에 대한 기대와 염원을 담은 하나의 부적과 같은 그림이라고 할 수 있을 것이다.

민화를 통한 이러한 근원적 가치에 대한 환기는 개인, 사회, 세계의 조화보다는 단절을 야기하며 오히려 개인의 삶에 대한 의미를 상실시키고 있는 오늘날, 오랫동안 인류가 잃어버린 오래된 질문을 상기시킨다.

전시는 조선미술과 동시대미술의 교차, 병치, 혼용을 통해 이 시대가 함의하고 있는 또는 요구하는 근원적인 가치에 대한 재고와 우리가 모던이라 부르던 시대에 그토록 찾아내고자 했던 ‘새로운 것’의 비전, 선형적인 ‘시간성’의 해체를 통한 현대성(mordernity)의 의미를 확장시켜 나가고자 한다. 아울러 전시는 전통과 현대, 주류와 비주류, 고급과 저급, 가상과 실재, 꿈과 현실, 삶과 죽음, 과거와 현재 따위의 이분법으로 제시되지만 결국 이것이 서로 밀고 당기며 양가적인 개념을 더 이상 구분하지 않을 때 민화의 시대 혹은 지금 이 시대가 욕망하는 새로운 세계, 두 개의 태양에 대한 가능성을 확인할 수 있을 것이라 기대하며 이상향이라는 주제의식을 통해 ‘새로움이란 무엇인가’ 라는 미학적 질문을 던지고자 한다.

전시 제목인 《황혜홀혜 恍兮惚兮》는 노자 도덕경 21장에 나오는 구절로 ‘홀하고 황한 가운데 형상이 있다’는 풀이에 비추어, 해가 뜨고 지는 여명기와 같은 그윽하고 어두운 가운데 실체가 있다는 의미로 해석하며 ‘이상향’ 이라는 보이지 않고, 존재하는 않는 세계를 사유할 수 있는 단서로 작동한다.

전시구성

인트로섹션 : 두 개의 태양太陽

Section1: 산山을 나는 바다

Section2 : 수수壽壽 복복福福

Section3 : 문자文字와 책冊의 향香과 기氣

In the modern and contemporary art of Korea, what the art circles in Joseon at the end of the 19th century demanded was not to overcome the then rampant feudality or acquire modernity but to drive the independence or self-reliance of people to take root, which was considered as the epic of aesthetic value. At the end of the 19th century or in the early 20th century, Joseon was subject to foreign invasion abroad and aggravation of class contradiction domestically. Thus, the aspiration for such aesthetic values further intensified with Joseon literary painting at the center of the zeal. Against this backdrop, Joseon made its port available for the first time to passengers and goods traveling to and from foreign countries, while going through rapid changes in the social class system. It then started to embrace the West-oriented modern art dynamics with a radical and narrow mindset of “equating the modernization to Westernization” without adequate reflection on traditional beliefs or informed interpretation on the new art. With a lack of tradition-based internal drivers in Joseon, there was a shift in attention from “calligraphy and painting” to the Western “art” at a time when Joseon was not free from outside socio-political conditions. Thus, “calligraphy and painting” along with “folk painting” known as the culmination of the calligraphy and painting in the 500 Years of Joseon Dynasty, in fact, failed to have their values historically solidified.

The term “folk painting” has been used up to date after being coined with the statement made by Yanagi Muneyoshi, a Japanese aesthetics scholar and activist of a folk-art movement to refer to the painting by and for ordinary people. True, currently, folk painting encompasses painting of commoners, decorative painting at court and court painting, but that unique, witty and wonderous figurativeness is embedded in folk painting as painting for ordinary people beyond its simple name’s sake is noteworthy. The figurative form of folk painting manifests picturesqueness which transcends abstraction and figuration through multiviews in deconstructing and overturning objects and even the trend of times to reflect the social aspects with many icons having their own meanings. Moreover, artists of folk painting are not professional painters, so instead of complying with certain socially regulated principles or rules, they seek for their own solutions by having their free will, which was crystalized in newer styles on the condition of anonymity. In particular, folk painting allows for suspected factuality, sophistication in expression, omission & distortion and even childish expression, because it is driven by the mindset in literary painting. Such a context can be easily found in the contemporary art later.

Folk painting is what embodies people’s ultimate and most humane wish in life by clinging to their secular desires without having any place to resort to in the rapidly changing era. The desires of the times to realize humans’ universal values – happiness, love, wealth, longevity and eternity – develop into yearning for a decent life or an ideal world, being expanded into a new world of folk painting. Folk painting also encompasses fundamental desires to contemplate on life and death of humans: harmony between humans and the nature, success and wealth/nobility, prosperity of descendants, heroic tales, good health & long life, and reality & dreams. Folk painters tried to emulate the sophisticated culture of gentry and appropriated their spiritual painting style, but the beauty of folk painting – unlike literary painting – is uniquely positioned through openness and anonymity. It is to depict the rapidly changing world of reality into dreams, belief and hopes for the future through the world of art carried from the ancient times as a historic tradition, and not to disregard or escape from the times. It is analogous to talisman-like painting with expectations and yearning for the new world. Recalling such fundamental values through folk painting induces disconnection instead of the harmony among the individuals, society and the world, and raises a question that has been asked for long, yet forgotten by the mankind in today’s world when means of individual lives are lost.

This exhibition is focused on revisiting fundamental values found in or demanded by the current times through the intersection, juxtaposition and combination of the 19th century Joseon art and the contemporary art, and expand the meanings of modernity by deconstructing the linear “temporality” as well as the vision of “novelty” we have sought to discover for long in the era we call “modern.”

Dichotomy is used for the comparison of traditions vs. modernity, mainstream vs. peripherals, high-class vs. low-class, virtuality vs. actuality, dreams vs. reality, life vs. death and past vs. present. However, it is expected that only when there is further distinction of push-pull ambivalent notions, we can identify possibilities of worlds – the times when folk painting thrived or the new world desired by the current generation – or “two suns.” “What is novelty?” is to be asked through the theme of an ideal world.

The Korean title of the exhibition “Hwanghye-Holhye” can be interpreted to mean the presence of a substance (“ousia”) amid vagueness and darkness just like a dawn where the sun goes up and down with a motif from Chapter 21 of Tao Te Ching, a Chinese classic text traditionally credited to the 6th-century BC sage Lao Tzu. It serves as a clue to think about a non-existent world.전시제목2021 근현대미술기획전《황혜홀혜 恍兮惚兮》

전시기간2021.06.25(금) - 2021.10.10(일)

참여작가 류성실, 양아치, 이진경, 전정우, 조인호, 전혜림, 최하늘, 황석봉, 백은배, 원성원, 김지평

관람시간3월 ~ 10월 ( 10:00 ~ 19:00 )

11월 ~ 2월 ( 09:00 ~ 18:00 )휴관일매주 월요일 휴관, 설날, 추석 당일, 운영상 휴관이 불가피하다고 인정하여 도지사가 지정하는 날

장르회화, 조각, 사진, 영상, 설치 등 60여점

관람료어른 1,000원(단체 700원)

청소년 및 군인 700원(단체 500원)

어린이 500원(단체 300원)

(단체 20명 이상)

장애인, 유공자, 65세 이상, 7세 미만 무료장소경남도립미술관 Gyeongnam Art Museum (경남 창원시 의창구 용지로 296 (퇴촌동, 경남도립미술관) )

기획이미영 학예사

주최경남도립미술관

연락처055-254-4600

Artists in This Show

경남도립미술관(Gyeongnam Art Museum) Shows on Mu:um

Current Shows