가짜, 가짜여야 하는, 가짜여야 되는 기분에 대하여 | 최수인 개인전 《Fake Mood》

가짜 기분. 쨍한 표현이다. 순도를 훼손당하지 말아야 하는 기분이다. “이 기분은 가짜”라고, 최수인은 꾹 눌러 말한다. 여기, 여기가 무대라고 한다면, 역할이 있다. 역할은 약속된 언어로 귀를 사로잡지 않는다. 디오니소스 축제보다 아득히 더 먼 태고의, 혹은 더 원시적인, 비극(悲劇)의 씨앗이 무드인 세계가 무대이고, 무대는 세계보다 협소하지 않은가란 질문도 필요 없게 여기서, 세계가 무대고 무대가 세계다. 여기에 “나”가 있는데 “나의 주변”이 있고 “나와 나의 주변”을 바라보는 눈이 있다. 말했듯 언어 없이, 망(望)은 있어서 바라보고 기대하고 노여워하는 원색 감각, 감정이 역할이다. 온몸으로 기쁘고 온몸으로 슬픔이 온몸의 만개한 움직임이 아니듯 잔뜩 머금은 상태 그 자체가 역할인 이 무대, 이 세계는 그러니까 가짜다. 그러니까 온마음 다해 공들이고 피하지 않고 피할 수 없고 부릅뜨고 맞닥뜨리는 여기가 가짜인데, 가짜라고 해도 나아짐은 없다. 이건 차도의 문제가 아니고 회복 거리도 아니다. 정도가 개입할 수 없고 개입이란 것도 소용없는 완강한 완연함이다. 망(望)이 있다 해도 풍경이 아니고 발끝이라도 이 세계에 속하는 한 역할이 있어서 풍경은 눈에 들어올 틈조차 없다. 최수인은 꾹꾹 눌러 다시 말한다. “풍경 아니고 상상화”라고. 상상을 그림으로 급히 수식한 상상화에 만족하지 않고 상상과 그림 모두에 압을 둔다면 역할화(役割畵)는 어떨까 생각해 보는데 그럼에도 최수인의 바람은 부름에 있지 않다는 것만은 확실하다. 부름은 궁리가 필요한데 풍경이 들어올 틈 없듯 생각의 틈도 여지없다.

나는 처음 상담가처럼 그녀를 찾았다. “나”, “나의 주변”, “나와 나의 주변”을 바라보는 눈에 대한 작업 노트를 읽고서 이 구성된 세계가 최수인의 세계에서 차지하는 지분을 타진하려고 했다. 계산된 의도가 결과값으로 도출된 것은 아닌가 일말의 의심을 품기도 했고 에테르같은 그녀 말의 크리스털화가 회화이지 않을까 막연히 추측하면서 말이다. 일상에서 이 무드가 어느 정도 영향을 미치는지 물었으나 이 말은 닿지 않았다. 우문일 뿐이었다. 상담자, 통역자, 번역자로 분석하고 해석하여 제 몫을 찾아주어야겠다는, 이 세계의 언어는 이미 깊은 세계의 골을 저 끝까지 내려가 이윽고 분리해 버리고 마는 몰이해라는 이해만을 낳겠구나. 그렇다면 최수인 지향(oriented)의 망(望)이 비록 가짜의 무대에서 만드는 갈등과 긴장에도 불구하고 이 무대의 습속과 역할임을 받기로 했다. 최수인은 그간 “스스로를 희생양으로 자처하는 주체간의 사이코드라마”를 캔버스에 펼쳤다. 사실 희생양과 주체는 의미에서 서로를 밀쳐낸다. 흘려 읽으면 그렇다. 그러나 작가는 자기 일이 무엇인지 안다. 우선 “스스로를 희생양으로 자처하는” 주체는 희생양이 아니고, 『희생양』의 저자 르네 지라르(René Girard)는 ‘희생양은 일종의 희생양이다’라고, 즉 희생양이라는 말은 희생양의 무고함과 함께 희생양에 대한 집단 폭력의 집중과 이 집중의 집단적 결과를 동시에 가리키고 있음을 짚는다. 옛 서사를 거듭 쓸 필요 없이 희생양이 있(었)으나 희생양이 아님(아니었음)을, 알면서도 벌어지고 마는 세계에 모두 산다. 야멸차면서도 거세게 몰아치는 생생한 가짜에 젠체하는 모조, 위조, 허상 같은 정련된 대체어는 가짜다. ‘그럼에도 불구하고’ 들이미는 가능한 희망 그리고 이성의 호소도 가짜의 세 옆에서는 하릴없다.

사이코드라마에서도 보조자에 의해 역할연기가 변하듯 이제 참여를 결심하면 나는 “나”일 수도, “나의 주변”일 수도, 바라보는 눈이 될 수도 있다. 전작(全作)들과는 달리 이번 전시 《Fake Mood》에서 “나”는 두드러진 자리를 차지하지 않는 대신 “나의 주변”이 “나”의 자리를 짐작하게 한다. 최수인의 입장에서는 캔버스 밖에 한 번 (숨어) 있는 “나”를 안에서도 한 번 (숨어) 있게 만드는, 두 번 있으면서 두 번 숨는 처지가 다소 번다할지 모르겠지만 역할을 최소화하려고 애썼다. 어려움은 “대상을 표현하면서도 주변을 포착해야 하니까” 생긴다고 말한다. 두 가지를 동시에 잘하고 싶다고 토로한다. 이 그리기에서 척이란 없다. 밑그림 없이 캔버스 전체를 장면으로 구상화하는 그림 앞에서 만약 눈 둘 곳 없다 느껴진다면 불편함이 싫어서일지 모른다. 상징 세계로 친절히 의미를 건네지 않고 파도, 나무, 구름의 형상 가까이까지만 허락하고 뿔과 이빨과 같은 돌기는 나를 대상으로 위협하는 듯하다. 삐죽삐죽한 모든 것 앞에서 좀처럼 편안하지 않다. 말단에 자리한 날카로움은 고양이 같은 공격성을 지닌다. 해치지 않으면 나를 해치지도 않을, 웅크리고 언젠가 뛰어오를 때 비록 그것이 티끌이라도 반응을 야기하는 찰나가 예비된다. 최수인에게 이 “찰나”는 중요하다. 찰나의 기시감이 내 세계와 조응을 이룬다면 불편함의 봉인은 풀리고 진입의 계기가 주어진다. 이 찰나를 예비하기 위해 고된 장면 그리기가 있다.

《Fake Mood》에서 시각적으로 가장 강렬해 보이는 〈살아있을 때 안 좋은 예〉는 맹수가 박제된 사진을 본 마음 상태에서 출발한다. 그러나 이 작품은 사진을 옮긴 게 아니다. 최수인의 구상은 도출된 이미지의 구체성이 아닌 구상 본연의 구성된 상에 해당한다. 죽었음에도 살아있는 것으로 느껴지는 “이 생명체의 마지막 꼴이 안좋아서” 이 감응은 이내 전이된다. 누구나 이렇게 될 수 있는 흐름이 살아도 산 것 아닌 죽어도 죽은 것 아닌 처지를 이입시킨다. “도깨비” 혹은 “정승”처럼 애달픈 형상은 ‘우울한 내용은 우습게 말하라(ridendo dicere severum)’는 라틴어 경구의 실사에 흡사하지 않을까. 〈Observer〉의 나무는 화면 중앙에 비스듬히 기울어 솟구쳐 올라 폭죽과 구름과 함께 하지만 찬란한 국면에 예감하는 하강이 나도 몰랐던 이염에 손댈수록 번져가는 국면과 같이 의지와 무관하게 펼쳐질까 조마조마하다. 염원은 전환이 아니라 유예의 긴 지속이라 지속만이라도 바라는 마음은 경계에 솟대를 세운다. 내게는 이 나무가 솟대로 보인다. 이 모든 구상을 물활론(Animatism)에 기대어 보는 것은 퇴행인가 반문하게 되지만 오히려 언어의 세계, 상징의 세계가 숨긴 절반 이상의 세계를 어딘가에서 발굴하고 싶어진다. 이 절실함이 최수인에게 가짜다라는 선연한 닻, 가짜여야 한다는 당위, 가짜여야 된다는 가능태를 직조하게끔 한다. 물활론적 세계관을 유아기로의 퇴행으로 간주하고, 따라서 어서 어른 되기의 종용은 그때 그 순간 놓아버린 경향들을 사교라는 위선으로 포장한 채 짊어지고 살게 만든다. 이 포장을 헤집어버린 ‘예술가는, 오늘날에는 대부분 소멸해 버린 인류의 모든 경향에 봉사한 것이다.’

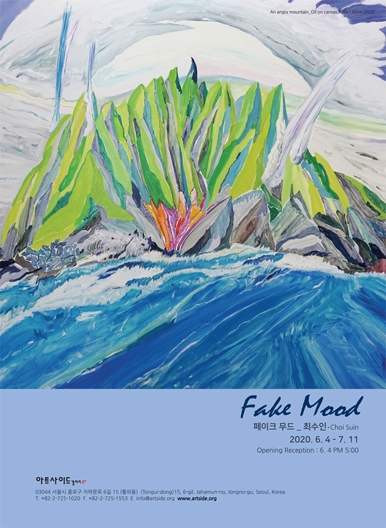

최수인은 《Fake Mood》에서 주체의 위치와 힘을 줄이면서 “더욱더 주인공을 농락하는 가짜 감정의 혼란을 가시화”하려는 시도와 더불어 색과 조형에 대한 관심을 가중시키고 있다. 그 계기로 작가는 “어느 순간 내가 그린 지옥이나 어떤 혼란이 어두운 색으로 표현되는 것이 아주 위선적으로 다가왔다”고 한다. 〈노란 기분〉이 흡사 파티의 한 장면으로 밝아 보이지만 동시에 “화가 나 있다”거나 〈An Angry Mountain〉이 새 봄 산세처럼 물오른 초목의 우거짐에도 갈고리같은 뿔이 나서 화가 나 있는 산이듯, 혼란으로 간주되고, 불쾌한 상태는 부정적이기 때문에 숨겨야 하는 이면으로 처리되지 않는다. 그녀가 좋아한다는 윌리엄스버그(Williamsburg)의 퍙숑 레드(Fanchon Red)를 두고 얘기를 나눴는데 이 물감의 발색은 작지만 흥미로운 단서로 여겨졌다. 이 붉은 색의 발색은 표면에서라기보다 흡사 배면에서 표면으로 올라와서 자리 잡는 발색처럼 느껴졌는데 이 느낌 또한 능동과 수동, 작용과 반작용, 긍정과 부정처럼 수순이 있고 위계가 있다는 믿음의 단편일지 모른다. 노란 기분은 노란 기분에 무수한 기분이 얽혀 있다. 최수인에게 노란 기분은 편향이 없다. 1%의 진짜를 숨겨둘 여지는 필요 없다. 가짜는 가짜로 둔다. 물타기는 가식을 낳을 뿐이다.

최수인은 자신의 작품을 통해 “책임감 없이 생각해 보는 시간”이 주어지길 바란다. 무책임하다 여겨질 수도 있는 발언으로 들릴지 모르겠다. 그러나 책임감이란 질서와 윤리에 따르는 감정이고 따라서 책임감을 갖는 것은 질서와 윤리를 내화했을 때 가능하다. “스스로를 희생양으로 자처하는 주체간의 사이코드라마”인 이 무대에서 희생양은 대속(代贖)의 제물이고 이때 애도가 희생양 도살의 책임을 면하려는 사회적 행위라면 대속과 애도는 책임감이 있어야만 했던 상황에 책임감을 면하려는 감정의 고양된 양태이다. 책임감이 있어서, 이 책임감을 면하려는 행위가 가짜로 구성된 진짜라고 믿는 세계라면 이제 많은 것들을 멈춰도 좋겠다. 소위 유치하고 유아적이고 무책임하게만 여겨지는 것들로 가득 찬 여기가 절대적인 세계라서 퇴각할 수 없고, 처음부터 이 세계 밖에서 이 세계는 깡그리 모르고 살지 않는 한 이미 도리 없는 전부임을 못내 수긍하는 게 그토록 어려운 일일까. 상담자, 통역자, 번역자로 언어를 가질 건가, 언어 없이, 망(望)이 있는 역할연기에 함께 할 것인가에 대한 결심에 대하여, 최수인은 “책임감 없이 생각해 보는 시간”을 건네고 있다.

■ 김현주

Fake, Must Be Fake, About Feeling of Being Fake

Choi, Suin’s Personal Exhibition Fake Mood

Fake mood. It’s a blazing expression. It’s the feeling of which purity must not be violated. Choi Suin says with lips tight, “This feeling is fake.”1) If this is on a stage, characters have a role each. But their role doesn’t seize audiences with promised words. In the dim and distant past, far earlier than the Dionysus festival ― in the further primitive times ― the world with seeds of tragedy opened a stage. And the question, ‘Isn’t a stage narrower than the world?’ is not necessary here: the world is a stage and a stage is the world. “I” am here and “my surroundings” are here. And there are “eyes looking at me and my surroundings.”2) On the stage, I harbor hope without language, so I look for, expect, and get angry. This is the role of raw emotions. A stage presents happiness with its own body, and radiates a blooming sorrow in its place. Thus, the world is fake. A stage does not avoid reality, but confronts it, opening its eye widely. But it is fake, and anything gets better though it is fake. This is not a problem of difference or a matter of recovery. Any extent can’t intervene in it. It’s just a perfect obviousness, for which any intervention is useless. Though there is hope, it’s not scenery. The stage is full of roles, so that scenery fails to be cast for even a tiny role in it. Choi says again with lips tight, “Not scenery but imaginary picture.” How about calling the stage a role painting, instead of the term, imaginary painting, that modifies imagination with painting? Surely, Choi’s wish is not in naming.3) Naming needs deliberation, but the stage that has no niche for scenery has no place for even thinking.

At first I met her like a consultant. Having read her writings about “I”, “my surroundings,” and “eyes looking at me and my surroundings,” I tried to measure how much these notions occupy in her world. I doubted for a while if her calculated intention was worked out as an output. I also assumed that her ether-like words might have been crystallized into painting. I asked her how much this mood influences her in daily life, but my question failed to reach her. It was a stupid question. As a consultant, interpreter, or translator, I had intended to help her find the share of these notions in her world by analyzing and interpreting her work. But I then realized that my attempt would give rise to a lack of understanding as I sank to the bottom of her world, disjointing it. Though Choi’s wish is conflict and tension that she creates on a fake stage, it must be admitted that they are attributes of her stage. So far, Choi has presented canvases describing a “psychodrama where main agents think of themselves as scapegoats.” In fact, a scapegoat and a main agent push away from each other in terms of their roles. It is so at a glance. But Choi knows what she should do. She understands that main agents who think of themselves as scapegoats are not scapegoats. René Girard, who wrote The Scapegoat, also stated: “Scapegoat is a kind of scapegoat.” That is, the word, scapegoat, points out both the concentration of collective violence against scapegoats and the collective result of the concentration, along with the innocence of scapegoats.4) We all live in the world where there are(were) scapegoats but they are(were) not scapegoats, needless to recall old narratives. Refined alternatives to vivid fake that sweeps in the world, too, such as imitation, forgery, and illumination, are all fake. The hope that, despite that, pushes itself to the world and the appeal of ration are hopeless next to fake.

As in a psychodrama, a role can be changed by an assistant, so you can be “I,” “my surroundings,” or “eyes looking at me in the world.” Unlike in Choi’s earlier pieces, “I” do not take a certain conspicuous role in the pieces of this exhibition Fake Mood. Instead, “my surroundings” took over the position of “I.” Though as for Choi, it may be a little troublesome to hide herself, who hides in the world, on the canvas, she tried to minimize her role. She states that it is hard for her to describe objects and seize the setting at the same time. She says that she wishes to do the two things well. Making a great painting has no pretension. If you feel that there is nothing to see on her representation painting showing a scene as a whole, it might be because you don’t like discomfort. Choi only allows audiences to reach up to symbolic shapes that look like waves, trees, and clouds, and the horns and teeth drawn on the painting seem like threatening us. We are not relaxed in front of jagged mountains, waves, and trees. The sharpness on the lower part of the piece also hold a catlike aggression. The cat wouldn’t hurt you if you don’t hurt it, but it preserves a moment that will make an reaction when given a chance to stretch out its crouched body. For Choi, a moment for reaction is important. If déjà vu in a split second accords with our world, the seal of discomfort is opened, and we are allowed to enter her stage. Choi has endured hard times to reserve this moment.

The thing that is not alive, a piece that looks most drastic of the pieces in this exhibition, was made after Choi saw a photo of a stuffed beast. She didn’t just copied the photo for her work. She didn’t objectify the image of the stuffed beast, but made a composition being true to the characteristic of representation. She was unpleased with ‘the end of a living thing,’ and her feeling of it was transmitted to her work. Watching this piece, we are bound to feel that any living thing can be treated like that ― it is living, but is not living, and it is dead, but is not dead. Heartrending shapes, like a goblin or a totem pole at the village entrance, recall the Latin epigram, ‘ridendo dicere severum.’5) The tree in Observer stretch up into clouds and fireworks, leaned aside. But the splendid scene drives us to anticipate the fall of the tree in a growing fear, regardless of our will. What we want is not transferring but a long suspension, so we set a pole of good luck for the work. For me, the tree in Observer looks like a pole of good luck. I ask myself, ’Is it regressive if I interpret all representation in terms of animatism?‘ Rather, I feel like discovering half of the meaning that is hidden by the world of language and the world of symbol.6) This desperation drives Choi to make an anchor that declares fake, justification that one should be fake, and potentiality that one may be fake. We live in the world that regards animatism as a regression toward infancy and urges us to grow up. So we are forced to live giving up the trends we missed in childhood, regarding them as pagans. Artists who bring these trends to the surface are ones who serve to obtain the validity of all the trends in the world.7)

For the pieces of Fake Mood, Choi tried to reduce the position and power of protagonists and to ‘visualize the confusion of fake emotions that laugh at them.’ In addition, she had an more interest in color and form. She says, “At some point, I felt that it was hypocritical that I expressed hell and confusion using dark colors.” She thus made Yellow mood that looks like a fun party but gives off a feeling of anger, and An Angry Mountain where green trees of spring stretch out their branches like hooklike horns. She doesn’t think that uncomfortable and unpleasant situations are negative sides that should be hidden in her work. I talked with her about the Fanchon Red of Williamsburg that she likes, and the development of the color left a little and interesting hint. The development of the red color appears to come up from the back to the surface, which led me to think that this feeling too may be an aspect of the belief that everything has two sides, such as activeness and passiveness, action and reaction, positiveness and negativeness. For Choi, a feeling of yellow is involved with numerous feelings. She has not bias against it. A margin is not necessary to hide 1% of genuineness. She puts fake as fake. Dilution only bears a pretension.

Choi wishes that there would be a time for audiences to think of something without responsibility through her pieces. It might sound irresponsible, but responsibility is a sense that follows order and ethics, so that taking responsibility is possible when accepting order and ethics. In the psychodrama where protagonists think of themselves as scapegoats, the scapegoats are atonement offerings, when mourning is a social act and a heightened emotional response to avoid the responsibility of killing the scapegoats. If we are in the world where we believe that the act to avoid responsibility that we have is true, I think it is fine to stop many things. I think we should withdraw from the world that is filled only with childlike and irresponsible things. Of whether I will choose to have language as a consultant, interpreter, and translator or to take part in playing a role harboring hope, Choi suggests me to have a time to think without responsibility.

■ Kim Hyunju

전시제목최수인 개인전: 페이크 무드

전시기간2020.06.04(목) - 2020.07.11(토)

참여작가

최수인

초대일시2020년 06월 04일 목요일 05:00pm

관람시간10:00am - 06:00pm

휴관일월,공휴일 휴관

장르회화

관람료무료

장소갤러리 아트사이드 GALLERY ARTSIDE (서울 종로구 자하문로6길 15 (통의동, 갤러리 아트싸이드) )

연락처02-725-1020