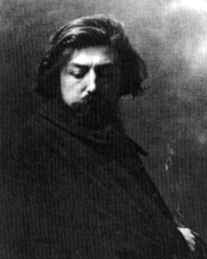

장 델비유(Jean Delville)FOLLOW

1867년01월19일 벨기에 뢰번 출생 - 1953년01월19일

장 델비유(Jean Delville)FOLLOW

1867년01월19일 벨기에 뢰번 출생 - 1953년01월19일

추가정보

During the last decades of the 19th century, many people in the West reacted to the materialism and hypocrisy of the period by developing an interest in esoteric, occult and spiritual subjects. The enthusiasm for these ideas reached its peak during the 1890s, the decade when the Belgian painter and writer Jean Delville was at the height of his powers. Delville was born in the Belgian town of Louvain in 1867. He lived most of his life in Brussels, but also spent some years in Paris, Rome, Glasgow and London. He began his training at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts when he was twelve, continuing there until 1889, and winning a number of top prizes. He began exhibiting professionally at the age of twenty, and later taught at the Academies of Fine Arts in Glasgow and Brussels. In addition to painting, Delville also expressed his ideas in numerous written texts.

Delville became committed to spiritual and esoteric subjects during his early twenties. In 1887 or 1888 he spent a period in Paris, where he met Sar Josephin Peladan, an eccentric mystic and occultist, who defined himself as a modern Rosicrucian, descended from the Persian Magi. Delville was struck by a number of Peladan's ideas, among them his vision of the ideal artist as a spontaneously developed initiate, whose mission was to send light, spirituality and mysticism into the world. He exhibited paintings in P?adan's Salons of the Rose + Croix between 1892 and 1895.

In 1895 Delville published his Dialogue entre nous, a text in which he outlined his views on occultism and esoteric philosophy. Brendan Cole discusses this text in his D.Phil. thesis on Delville (Christ Church, Oxford, 2000), pointing out that, though the Dialogue reflects the ideas of a number of occultists, it also reveals a new interest in Theosophy. Sometime during the mid to late 1890s, Delville joined the Theosophical Society, and in 1910 he became the secretary of the theosophical movement in Belgium. In the same year he added a tower to his house in Forest, a suburb of Brussels. Following the ideas of Krishnamurti, Delville painted the meditation room at the top, including the floorboards, entirely in blue. The Theosophical emblem was placed at the summit of the ceiling. But though photographs and drawings still exist, the house, regrettably, no longer stands.

In his biography, Delville's son Olivier tells us that his father, determined to pass his ideals on to the world, was continually painting and writing. He supplemented this unreliable income by teaching art. But his busy professional life did not prevent him from applying his strongly held beliefs to his personal life. Olivier describes his father as a person of courage, perseverance, probity and intellect, as well as an upright family man who was strict with his six children.

Despite all his work and ability, however, Delville never achieved the recognition he would have liked. As Brendan Cole says in his thesis, he almost certainly paid a price for refusing to compromise his ideals. By 1951, Delville had become almost completely ignored and forgotten. He died two years later and did not live to see the revival of interest in his work. This was marked by exhibitions in London in 1968, and Paris in 1972. Today Delville's pictures (especially the early ones, up to the First World War) are once again recognised for their unusual qualities. Although they do not correspond with everyone's taste, many people now see them as outstanding and fascinating expressions of otherworldly subjects. In this context, they are often included in exhibitions and anthologies of the Symbolist movement, and books on fantastic and esoteric art. Delville's works are also remembered at the Theosophical Society headquarters in Madras, where the Hall of Religions was decorated during the 1960s in a style which, according to Philippe Jullian, imitates that of Delville (The Symbolists, 1973).